Is interdisciplinary research on the rise?

Efforts to enhance interdisciplinary research and teaching have grown substantially over the past fifty years. But are they working?

This is the first post in a new project, Bridging Boundaries, a new “living literature review” on interdisciplinarity, supported by Open Philanthropy.

You can read more about the project here, and sign up for the newsletter to receive updates below.

—

Disciplines fuel the modern world. Whether structuring universities, shaping industry, or informing policy, disciplinary divides have helped organize most of humanity’s institutions throughout history.

But the consensus today is that these boundaries are often a barrier to progress and innovation. This has driven a longstanding movement to break and bridge these divides through interdisciplinarity.

Writing in 2000, Weingart and Stehr identified interdisciplinarity’s rising appeal, finding the term to generally “denote reform, innovation and progress” (p.xii). Fast forward several decades, and Repko, Szostak and Phillips (2020) find that the academy largely views interdisciplinary to be superior to the alternatives in most research settings. They remark, “[t]oday, disciplinarity dominance is being challenged by interdisciplinarity” (p. 27). They echo Porter and Rafols (2009)’s pronouncement that “[i]nterdisciplinary research seems almost universally acclaimed as “the way to go’” (p.2).

Growing calls for interdisciplinarity have been backed, in some places, by billions of dollars. The National Science Foundation, a large U.S. government research funding body for the non-medical sciences that disbursed $9.9 billion in 2023, writes on its website that it “gives high priority to research that is interdisciplinary — transcending the scope of a single discipline or program.”

But have these efforts worked? Has interdisciplinarity risen commensurately in response to these calls? How is interdisciplinarity measured, and is it indeed on the rise?

Is interdisciplinarity increasing?

Without agreed definitions and metrics to guide study design and replication, there are limitations in our abilities to measure and track interdisciplinarity in practice. Still, a growing number of studies help illustrate how interdisciplinary research has expanded over time and some of the limitations at play.

While definitions differ, interdisciplinarity primarily aims to bring approaches from multiple fields of study together, often through collaborative research modalities, and usually with a desired outcome to produce insights relevant to multiple fields. Aboelela (2006) in their systematic review of definitions and practices of interdisciplinarity find three primary characteristics of a common understanding of the concept, based on: the qualitative mode of research (and its theoretical underpinnings), existence of a continuum of synthesis among disciplines, and the desired outcome of the interdisciplinary research.

Stirling, 2007 suggests that efforts to measure interdisciplinarity require at least two forms of measurement surrounding the quality and quantity of disciplinarity inputs: “A satisfactory index needs information on the variety of disciplines, their balance (or relative frequency) and their disparity (the ‘distance’ between them).”

Two common metrics frequently deployed in studies that aim to track these characteristics include:

· Co-authorship: Co-authorship is on its own an indicator for collaboration and innovation. A more refined metric for interdisciplinarity measures the disciplinary homes of co-authors both qualitatively and quantitatively. Moody, 2004 uses co-authorship as a metric, for example, to study interdisciplinary research rates in sociology.

· Citation characteristics: Another common metric of interdisciplinarity tracks the disciplinary homes of citations inside a given publication. Researchers use a variety of approaches tracking how often academics cite research that is distinct from their disciplinary home, how close or far these disciplines are, and how many disciplines, in total are cited. Raasch et al, 2013 use measures that quantify the numbers of citations outside the author(s) home disciplines as a metric alongside co-authorship in their study on interdisciplinary research rates in open-source research.

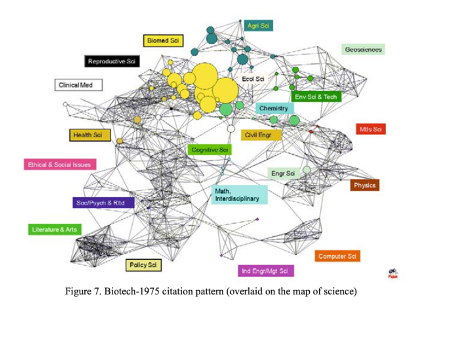

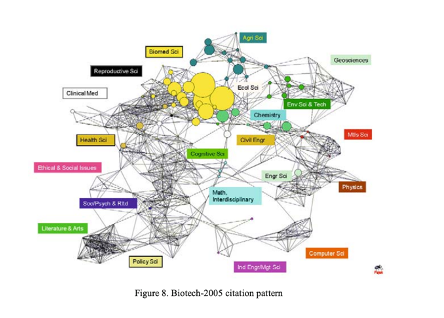

What is the best evidence on rates of interdisciplinarity? A significant study from Porter and Rafols (2009) found that interdisciplinary research in the sciences was grew over thirty years by about 50%. Their study specifically explored six scientific research domains from 1975-2005. Using the metric of co-authorship, a surface investigation found a whopping 75% increase over the period in the degree of interdisciplinarity among co-authors for research papers reviewed. However, when digging deeper into the data, the increase in research collaboration was overwhelmingly occurring among “neighboring fields” that is, for example, a common collaboration in research bringing together sub-fields of science, but much less often bringing fields that are more distant together (such as hard sciences and social sciences, or sciences and humanities). Their measure of instances of interdisciplinarity that brought together researchers outside of neighboring fields was low, only about 5%. This was true even in newer fields, such as biotech, which initially emerged as a type of “interdisciplinary” field that brought together engineering and biological sciences. Their mapping of trends in biotech (figures 1 and 2 below) finds the field broadly nested in the macro-field of biomedical sciences, although new interactions emerge – for example, in 2005, there is an uptick intersection between biotech and materials science. Overall, they found that “science is indeed becoming more interdisciplinary, but in small steps.” The authors suggest calls for interdisciplinarity have had limits in practice, mainly achieving gains in connecting neighboring fields, with only modest gains in connecting fields that are otherwise far apart.

Figure 1.

Figure 2

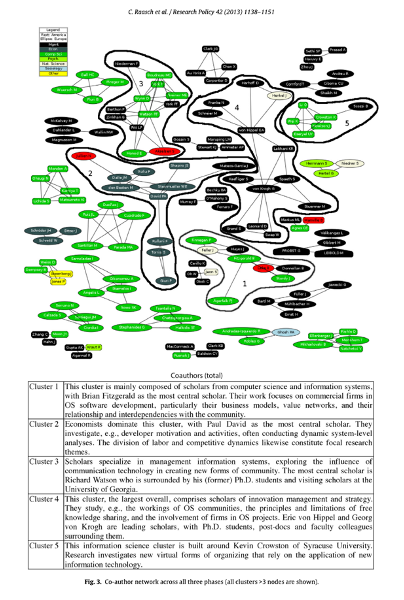

Raasch, Lee, Spaeth and Herstatt (2013) offer another view into the question, with somewhat similar results. They look specifically at the field of “open source” research, or research of publicly available information, and find some sticky limitations holding back a fuller expansion of interdisciplinary research in practice. They also find some areas where interdisciplinarity is on the decline. Using bibliometric and secondary data of 306 core open-source publications and over 10,000 associated reference documents over the period of 1999-2009, they report some decreases in interdisciplinarity in open-source research over the period reviewed, and highlight, a “tendency to return to disciplinary research.”

Even though their study focused on the sub-set of publications that are “open source” research, they believe their findings could be more widely generalizable. They point to similar findings in other fields – such as in entrepreneurship research (Landstrom and Lohrke, 2010) and strategic management (Nerur et al., 2008), that have documented a degree of increased fragmentation and separation into more homogenous disciplinary communities in a number of research communities

Figure 3

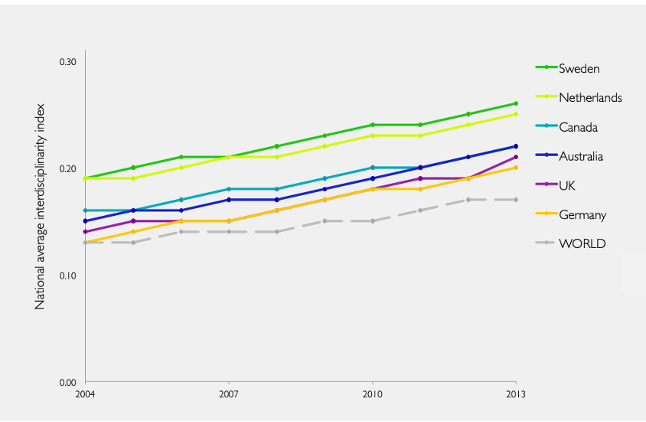

What do these trends look like from a global comparative perspective? Adams, Loach and Szomszor (2016) interrogate indicators of “interdisciplinarity,” and present indices of “multidisciplinarity” (research bringing two or more disciplines together) and “interdisciplinarity” (research that has cross-disciplinary outcomes) across funding/grants and publication outcomes. Comparing rates in the UK, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and Sweden, they find differential rates of interdisciplinary collaboration, with Germany sitting on the lower end and Sweden and the Netherlands on the higher end (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Finally, a study of Chinese academic papers spanning 106 disciplines from 1992 to 2022 from Rong et al, 2024 found an increase in interdisciplinarity in Chinese research. They identify that that 85% of disciplines saw what they call “critical years” where qualitative increases in interdisciplinary research (measured in cross disciplinary citations outside of the home discipline of the author(s)) occurred.

Are students learning more disciplines?

Trends in interdisciplinary research inform, but do not determine, related trends in interdisciplinary study. This data is variously measured in student exposure to interdisciplinary courses (measured by course enrollment) and by looking at data on the numbers of students who major in explicitly interdisciplinary majors. Again, definitions and metrics differ. Some examples of “interdisciplinary” majors include the study of cognitive science (combining, psychology, neuroscience, and linguistics), gender studies (combining history, social sciences, and literature), and environmental studies (combining physical and social sciences).

Through the 1970s, universities implemented a range of “new” majors and course tracks that encouraged interdisciplinary study among student bodies. In the United States, Deloitte’s “Data Studies” documented an increase in interdisciplinary studies graduates (of interdisciplinary majors) in the workforce by 2.68% from 953,786 in 2021 to 979,354 in 2022. This was while the number of overall college graduates slightly reduced from 2021 to 2022 in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic (National Center for Education Statistics). Deloitte’s study found that the largest single share of these graduates they labelled as “interdisciplinary” holding majors went to work as schoolteachers, though career trajectories of this group were unsurprisingly diverse.

A 2019 study by College Factual reported in 2019 that interdisciplinary studies was the 13th most popular major nationally in the U.S., and saw a 4.3% increase from the previous year.

Implementing interdisciplinarity teaching through courses and majors in practice has its limits. One study of the implementation, and demise, of an experimental interdisciplinary writing course at the University of South Dakota (Hoodman and Huckfelt, 2014) found that one challenge in interdisciplinary teaching in practice is when instructors are “trying to do too much” all at once. They recommend in evaluating their course that the “mandated skills and requirements should have been fewer.” The complexity of interdisciplinary teaching can mean that both faculty and students can struggle to get on the same page, structure learning, and gain necessary skills when multiple disciplines are brought to instruction all at once. There is a rich literature on good practices for interdisciplinary teaching (a subject for another post).

What explains these trends?

“Many researchers know interdisciplinarity when they see it, but not all see the same thing, and that makes life difficult for research funders and policy makers”. – Adams et al, 2016

It is perhaps surprising that interdisciplinary research that goes beyond connecting neighboring fields are not increasing more. This suggests relatively powerful barriers may be at play, given that the motivators are strong: research suggests that interdisciplinary researchers attain better long-term funding (Sun, Livian, Ma and Latora, 2021) and have greater impact (Okamura, 2019). Students exposed to interdisciplinary learning may also go on to make more money, especially for those in the sciences (Han, LaViolette, Borkenhagen, and Bearman, 2023). A detailed discussion about these studies and the question of the motivations and impacts of interdisciplinarity will come in a future post.

Part of the challenge may be one of effective measurement. For research, bibliographic analysis alone is often relied on as a metric, but Adams et al, 2016 have suggested this has missed other forms of collaborative inquiry. Are peer reviewers engaged in multiple disciplines? Have researchers engaged with multiple sectors in policy/research to disseminate their findings? A number of other factors could inform the ways that research could cut across disciplines across the research lifecycle beyond authorship and citation metrics.

Another challenge may lie in institutional arrangements. Many prominent U.S. institutions promoted interdisciplinarity through structural reforms – notably the University of California’s Commission on General Education and Harvard University’s reforms in the 1970s that offered interdisciplinary courses and curricula spanning multiple fields. Klein (1996) found that by the turn of the 21st century the number of interdisciplinary programs had declined since the 1970s. But Klein argued but this missed another trend, whereby interdisciplinary activities were occupying larger amounts of staff time even when organizational charts did not formally place people in interdisciplinary functions. This had both advantages and disadvantages. This reflects a point made by Clayton (1985) documented in Chettiparamb (2007) that “overt interdisciplinarity” may not make the same gains as “the concealed reality of interdisciplinarity” that sometimes flourishes beneath “subject facades.” These insights form an argument that for a true understanding of interdisciplinarity and its benefits, research must track not only formal organizational structures and outcomes, but also informal practices such as network building, consultations and exchanges, and other areas where interdisciplinarity can take root and benefit research.

There are various structural barriers impeding interdisciplinarity in practice. These barriers pose critical questions about the potential for expansion in interdisciplinarity and will be discussed with focused attention in posts to come. Scholars point to the absence of established benchmarks in emerging interdisciplinary fields, biased assessments, and rigidity stemming from the structures and incentives driving discipline-based journal publishing as roadblocks to the implementation of interdisciplinarity in practice (Jacobs & Frickel, 2009; Li & Chen, 2020; Pfirman & Martin, 2010).

Final thoughts

This post posed the question: is interdisciplinarity growing? Relatedly, it investigates, is the ongoing attention to and acceptance of the practice in contemporary academic and industry discourse making a difference?

Interdisciplinarity is not on an inevitable rising trajectory, even though there is widespread recognition of its benefits. Across some metrics, specifically those measuring the degree to which scientific studies are broadening out to incorporate adjacent fields, there have been measured increases documented. Interdisciplinary studies appear to be enjoying modest but steady increases in present-day. But accounting across a variety of measures, interdisciplinarity faces ongoing hurdles to meet many institutions’ stated ambitions, especially for bringing distant fields together. Some metrics even mark a decline and retrenchment towards disciplinary fragmentation.

That said, metrics and studies are relatively limited. There remain opportunities for researchers and practitioners to more deeply interrogate trends in interdisciplinary research, the factors that drive it, and obstacles facing its delivery in practice.

Articles Cited

Adams, J., Loach, T. and Szomzor, M. (2016). Digital Research Report: Interdisciplinary Research - Methodologies for Identification and Assessment. Digital Science.

Boyer, E. I. (1981). The quest for common learning. In Common learning: A Carnegie colloquium on general education (pp. 3–21). Washington, DC: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Learning.

Chettiparamb, A. (2011). Inter-Disciplinarity in Teaching: Probing Urban Studies. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 6(1), 68–90.

Clayton, K. (1984) Remarks at International Seminar on “Interdisciplinarity Revisited”. Linkoping, Sweden, 5th October.

Goodman, B.E., Huckfeldt, V.E. (2014) The Rise and Fall of a Required Interdisciplinary Course: Lessons Learned. Innov High Educ 39, 75–88.

Frank, R. (1988) Interdisciplinary: The First Half Century. In Stanley, E. G. and Hoad, T. F. WORDS: For Robert Burchfield’s Sixty Fifth Birthday. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, pp.91- 101.

Graff H. J. (2016) The “Problem” of Interdisciplinarity in Theory, Practice, and History. Social Science History. 2016;40(4):775-803.

Jacobs, J. A., & Frickel, S. (2009). Interdisciplinarity: A critical assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 43-65.

Klein, J. T. (1996) Crossing Boundaries: Knowledge, Disciplinarities and Interdisciplinarities. London: University Press of Virginia.

Landstrom, H. Lohrke, F. (2010). Historical Foundations of Entrepreneurial Research

Edward Elgar Pub., Cheltenham, UK.

Li, C., & Chen, H. (2020). Transformation of knowledge production mode and crisis of peer review. Journal of Higher Education Research, 41(12), 22-29.

Moody J. The structure of a social science collaboration network: Disciplinary cohesion from 1963 to 1999. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(2):213–238.

Nerur, S. P., Rasheed, A. A., & Natarajan, V. (2008). The intellectual structure of the strategic management field: An author co-citation analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 29(3), 319–336.

Pfirman, S., & Martin, P. J. S. (2010). Facilitating Interdisciplinary Scholars. In R. Frodeman, J. T. Klein, & C. Mitcham (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity (pp.387-403). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Porter, A., & Rafols, I. (2009). Is science becoming more interdisciplinary? Measuring and mapping six research fields over time. Scientometrics, 81(3), 719–745.

Raasch, C., Lee, V., Spaeth, S., & Herstatt, C. (2013). The rise and fall of interdisciplinary research: The case of open source innovation. Research Policy, 42(5), 1138-1151.

Repko, A. F., Szostak, R., & Buchberger, M. P. (2020). Introduction to interdisciplinary studies (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Rong, G., Ma, F., Qian, Y., Zhang, Z., Chen, S., & Sun, Y. (2024). Exploring the critical years for interdisciplinary citations. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24940

Stirling A. (2007). A general framework for analysing diversity in science, technology and society. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface, 4, 707-719.