Interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary research - what's the difference?

If combining disciplines matters, is there an optimal model?

This living literature review explores the growth of interdisciplinary research, measures of interdisciplinary research use and impact, and innovations for disciplinary collaboration.

But what exactly is interdisciplinary research? And how does it differ from other, related terms?

In practice, term “interdisciplinary” is poorly defined - as are its distinctions from related terms like “multidisciplinary” and “transdisciplinary.” Literature raises a variety of criticisms about the subjectivity and lack of utility of related definitional exercises (see some of these critiques below - my emphasis added):

“The academic literature on interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity shows no agreement over definitions. It shows plurality, heterogeneity and overlapping terms, even contested and contrasting discourses. Diverse definitions of inter- and transdisciplinarity coexist within the literature and are reproduced by researchers and practitioners.” – Vienni-Baptista, 2023

“…the highly subjective nature of these terms makes it difficult to see the difference between the categories, with the result that they are often used interchangeably…” – Newman, 2022

“Research in the multidisciplinary–interdisciplinary–transdisciplinary environment is not a set of mutually exclusive categories. Research is too complex…to be put into boxes that ignore the particularities of context…” – Klein, 2008

“The endless typologies, classifications, and hierarchies of multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinarities are not helpful” – Graff, 2015

Despite clear concern among scholars about the limited utility of these terms, studies continue to work to define and raise distinctions between forms of disciplinary collaboration. Current research includes work to explore when certain types of collaboration are optimal, and to map relative benefits and drawbacks of different boundary-spanning approaches.

This post summarizes prominent existing definitions of these terms and presents current knowledge on the comparative benefits of different approaches.

Image source: OpenLearn

Interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: What’s the difference?

One prominent source studies draw on to clarify distinctions between these categories is the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which sets out the following definitions for terms (as covered in Klein 2017):

Multidisciplinarity (OECD) Refers to“juxtaposition of various disciplines…[and] fosters wider scope of knowledge, information, and methods. Yet, disciplines remain separate, retain their original identity, and are not questioned.”

Interdisciplinarity (OECD) Refers to “simple communication of ideas to the mutual integration of organizing concepts, methodology, procedures, epistemology, terminology, data, and organization of research and education”

Transdisciplinarity (OECD) Refers to “[a] common system of axioms that transcends the scope of disciplinary worldviews through an overarching synthesis”

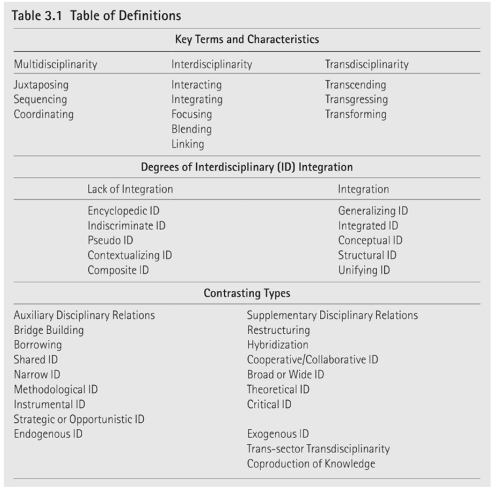

These definitions center the distinctions between terminologies around three potential characteristics: “integration” (for interdisciplinarity), “juxtaposition” / “separation” (for multidisicplinarity), and “transcendental” (for transdisciplinarity). Klein, 2017 sets out these distinctions, with cognates and other sub-categories, in Figure 1, which highlights how these efforts variously bring together disciplines from applying multiple disciplines but keeping them distinct, to focusing on blending these, to transforming the interaction to create something new.

Figure 1

Source: Klein 2017, in Frodeman et al, p. 22

Klein also provides a range of categories and a typology to explore the degree to which interdisciplinarity is integrated into research approach, methods, and process (not covered in detail in this post but with concepts to be focused on in future posts).

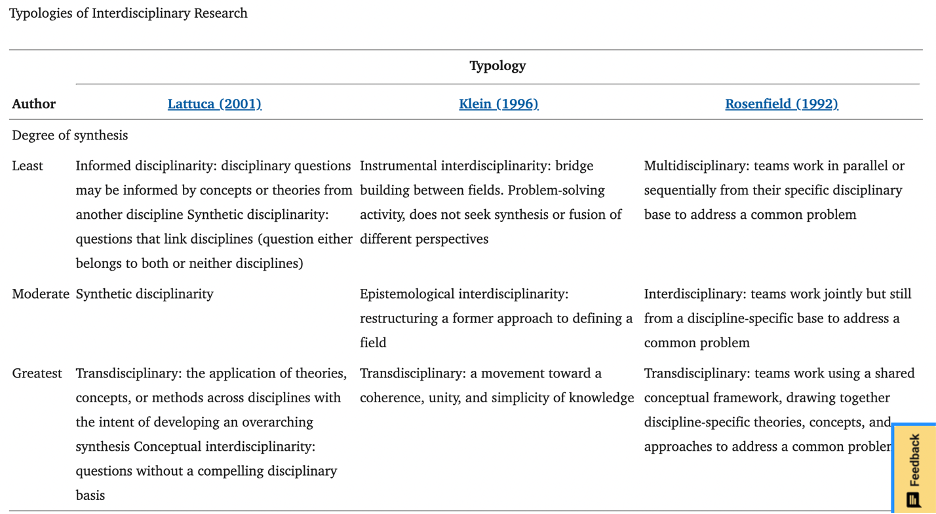

Another prominent source mapping these distinctions stems from a systematic review (Aboelela et al, 2007) which explored a spectrum of approaches based on their degree of “synthesis,” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Source: Aboelela et al, 2007

This model considers low-synthesis approaches to disciplinary collaboration (including “instrumental” interdisciplinarity), where research can be informed by different perspectives, to moderate-synthesis approaches (including “epistemological” interdisciplinarity) where approaches are re-structured, to high-synthesis approaches that work on synthesizing and fusing approaches.

Some questions one might consider in light of these studies when designing collaborative research teams drawing on multiple disciplines:

How separate are the teams and processes for input in research based on discipline?

To what degree are theories, concepts, frameworks, methods, and epistemologies blended across disciplines or distinct?

Is collaboration focused on collation of disciplinary ideas, bridge-building, or transformation?

Are certain forms of disciplinary collaboration more impactful?

Given these approaches and terminologies, is one version best? Which type of research is most impactful? And what are the advantages of different types of disciplinary research collaborations?

Studies remark confidence that crossing disciplines, sometimes connected to “boundary spanning,” can bear multiple benefits for research, including by advancing innovation and societal impact. But this type of disciplinary collaboration through research is also sometimes difficult to pursue, develop, and disseminate. There remains very limited research that fully evaluates the impacts of these different types of collaborations.

Some benefits to multi-disciplinary research over more integrated and synthesized models appears to be the maintenance of traditional forums and pathways for academic quality and recognition. Research from Zuo and Zhao, 2018 finds that more multidisciplinary institutions are not necessarily more collaborative, although they do feature collaborations that are more interdisciplinary.

Interdisciplinary research is often perceived as “riskier” as opportunities for publication and academic recognition are less established than research that sits clearly within a discipline, though sometimes early career researchers are more apt to take these risks as they are seeking collaboration and publication opportunities (Rhoten and Parker, 2004).

Leahey, 2017 finds that interdisciplinary research sometimes takes longer and has a “productivity penality” due to the “required time for learning of new concepts, literatures, and techniques, and communication difficulties within interdisciplinary teams”. Leahy particularly finds peer review to serve as a barrier for interdisciplinary methods, “because interdisciplinary offerings get caught in the middle and cannot be viewed and evaluated clearly”… which “scholars to navigate the peer review system and publish IDR [interdisciplinary research].”

Despite barriers and challenges, the payoff for interdisciplinary models can be big. One study finds that it is easier to gain grant funding for interdisciplinary research projects as a result of rising demand by funding agencies (Brown, Deletic, and Wong, 2015). Another study found that interdisciplinary researchers are more likely to find a job after completing their PhD than those based in a single discipline (Rhoten and Parker, 2004). Leahy, 2017 finds that, though interdisciplinary researchers are less prpoductive, they are more prominent (as indicated by citation counts).

The most integrated and transformational approaches of transdisciplinary research are lauded as potentially bringing the biggest payoffs – a “powerful tool for societal change” (Research on Research Institute, 2024). But these potentially require the most resource intensive supports. They usually include academic and nonacademic partnerships, values driven approaches, and societally impactful outcomes (Woods et al 2024), but usually demand even more intensive resources and time for deep collaborations and receive less support than lighter approaches to interdisciplinary work may require.

Optimal models : What does the literature recommend?

Avoid imprecision

Scholars lament the current imprecision in existing use of terminologies related to disciplinary boundary crossing. Choi et al in 2006 made the recommendation that appears to continue to ring true to avoid these categories unless they are precisely used. “Multiple disciplinary” as a broader term for disciplinary collaborations could offer a generalist concept that avoids incoherence from overlapping terms.

“We further propose that when the exact nature of a multiple disciplinary effort is not known, the specific terms “Multidisciplinary”, “interdisciplinary”, and “transdisciplinary” should be avoided, and the general term “multiple disciplinary” used instead.” – Choi et al 2006

Align approach to goals

Is the goal to maximize impact across sectors? Is it to promote certain forms of network building? Is it to support a researchers’ personal career growth and trajectory? Different levels of integration bring different benefits and drawbacks. Tracking and expanding the research on the relative benefits can help inform researchers in strategies for collaboration.

Consider best practices and look to expand necessary supports

A 2006 AAAS symposium for funding agencies (as discussed in Klein, 2008) considered some of the supportive requirements for evaluating and forming interdisciplinary research collaborations. Their recommendations include the use of “on-the-fly” electronic review teams, interpreters to bridge the epistemic gap among content experts, forming joint panels and “matrix” schemes that combine disciplinary reviews with interdisciplinary panels. They seek to “achieve equilibria between the familiarity and distance of non-expertise, between transparency and opacity, expertise and subjectivity, and between interdisciplinary appeal and disciplinary mastery.”

Supportive structures across research funding, evaluation, formation, and dissemination all appear necessary, and more time and resource intensive, and the requirements for such supports will depend on how deeply integrated and synthesized approaches aspire to be. Multidisciplinary approaches may suit best when resources and time are limited. More interactive approaches may bear stronger fruit when supportive environments are available across the research cycle to optimize impact.

**

This post will be updated as a “living review” to capture future research.

Think something is missing? Interested in co-writing a future post or sharing your experiences and insights? Reach out to me rageorge@stanford.edu and would be eager to include your contributions.